Margaret Bedggood - The Legal Luminaries Project

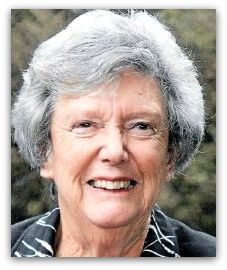

This is the second of a series of in-depth interviews with our esteemed legal leaders; our legal luminaries. Professor Margaret Bedggood, QSO looks back over her life in the law, speaking candidly about her achievements, offering advice for younger lawyers and discusses what she thinks are the most important legal issues right now.

This is the second of a series of in-depth interviews with our esteemed legal leaders; our legal luminaries. Professor Margaret Bedggood, QSO looks back over her life in the law, speaking candidly about her achievements, offering advice for younger lawyers and discusses what she thinks are the most important legal issues right now.

About The Legal Luminaries Project

In any sphere of human endeavour there are people whose sustained, consistent, and informed contribution within their specialist field of knowledge forms the foundation for those following in their footsteps. They are luminaries. The debt we owe them is incalculable as it is their work literally lighting our way forward.

The Legal Luminaries Project acknowledges the legacies of our esteemed legal leaders and seeks to give an overview of, and insight into, their lives within their specialist fields; to shine a light on the core values, thinking and events underpinning their successes.

Methodology

The information in each profile was collected over a series of interviews. The subjects covered and/or the questions asked appear ahead of their answers. Each of those is prefaced in bold with the interviewee's name: e.g. Margaret.

Professor Margaret Bedggood

A brief background

A brief background

The focal point of Margaret Bedggood’s life in law is Human Rights – a field in which she is both a teacher and activist.

She was the Chief Commissioner of the New Zealand Human Rights Commission (1989 – 1994) during which period the Human Rights Act 1993 was enacted. She has also been the Chairperson of the Management Committee of the Human Rights Foundation of Aotearoa New Zealand, an independent, broadly based human rights NGO.

She has been a member of Amnesty International since 1968, was previously Chair of its New Zealand section and a member of its governing body the International Executive Committee form 1999 to 2005.

She was a member of the Refugee Council, and has a long-standing interest in social justice issues within the Anglican Church, as a member of the Third Order of the Society of Saint Francis.

Margaret has taught law and classics in a variety of institutions and jurisdictions and is published on tort, employment law and human rights. She was the Dean of Te Piringa/ the University of Waikato School of Law from 1994 to 1999.

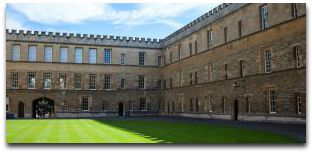

She continues to teach Masters Papers in International Human Rights Law at the University of Oxford, UK.

She continues to teach Masters Papers in International Human Rights Law at the University of Oxford, UK.

Academic & Awards

University of Auckland (MA Latin 1st Class Hons 1960)

University College, London (MA 1964)

University of Otago (LLB 1978)

University of Waikato Honorary Doctorate 2010

QSO for Public Service 1993

NZ Suffrage Year Centennial Medal 1993

Fullbright Travel Award – Visiting Scholar University of Michigan Law School 1987 – 88

Visiting Scholar St. John’s College, Oxford (April – August 1987)

University National Scholarship 1956

Contribution to law

– If you viewed your career in the law as an outsider, what would you say your main contribution or legacy was?

Margaret:

I think one of the most significant roles in my career was when I was Chair of the Human Rights Commission, working together with many others on steering the passage of the Human Rights Act 1993 through Parliament.

I think one of the most significant roles in my career was when I was Chair of the Human Rights Commission, working together with many others on steering the passage of the Human Rights Act 1993 through Parliament.

In essence the Act was a “tidy-up”: a consolidation, an amendment, and significant expansion of the Race Relations Act 1971 and the Human Rights Commission Act 1977. It came into force on 1 February 1994. It governs the work of the New Zealand Human Rights Commission and outlaws discrimination on a wide variety of grounds, including: sex (plus pregnancy and childbirth), marital status, religious or ethical belief, colour, race, ethnic or national origins, disability, age, political opinion, employment or family status, and sexual orientation.

There were three principal groups involved: the Commission, the Ministry of Justice and various interested NGOs. This was ground breaking legislation we were working on – including marginalized groups like those with disabilities or who were gay. It was a very interesting political exercise, and for me something entirely new.

There was some opposition to the inclusion of sexual orientation in the grounds on which discrimination would be illegal. The majority of the people I was working with, including myself, felt the Act would have been a mockery without the inclusion of all groups. You can’t have a Human Rights Bill where some people have more rights than others.

Sexual orientation was not included in the main Act, but in a Supplementary Order Paper from the Honourable Katherine O’Regan, which was then linked to the principle Act.

There was a secondary benefit though. The impassioned discussion and debate over the issue raised the Bill’s profile, making it a genuine stepping stone towards equality.

The difference the Act made

Finally anti-discrimination became the supported legal standard. It represented an evolution in our society. We’d come to a tipping point where what previously would have drawn censure and outrage was in the process of becoming normal. Even though the actual outward manifestation of change itself is gradual, the law supporting it was in place. Its influence would trickle down from the law to the street becoming an integral part of our lives.

There’s a right time for some social legislation and it was this Bill’s right time then. If we’d moved too quickly, or too soon, the Bill would have failed; backfired because it was too radical, and too threatening. However everything aligned: the time, the support of the government and the Minister of Justice and because the Labour Party was in opposition, there was none, or very little.

Early years

Margaret:

Black letter law followed by labour law

The beginning was a solid training in “black letter law” by which I mean torts and contract law. Following that I began as a lecturer specializing in labour law at the Faculty of Law, University of Otago. At that time (mid 1980s) employment or labour law did not have the status as a law discipline it has now. Then it was largely the province of lay people and any negotiations were mostly undertaken by the state, employers and unions. Lawyers were not so involved. As a consequence employment law had a relatively lowly status within schools and was often allotted to junior staff. In this instance, me.

By an extremely lucky stroke I met and worked with the brilliant pioneer of labour law in New Zealand, Professor Alexander Szakáts, who was at Otago too.

Over time though the field became more mainstream.

... scarcity created a perfect opening for me.

That coincided with a major societal shift. By the time the end of the 80’s came around women were becoming more influential and prominent in leadership positions. Now people were actively looking for those with experience and authority in the respective fields. Given their historical place in society there were comparatively few. That scarcity created a perfect opening for me.

I was invited to apply for the Chief Human Rights Commissioner’s job in 1988, a position I subsequently held from 1989 to 1994.

I knew the law didn’t work for everyone and saw it as an opportunity to do something about it. And by then my children had grown and I was able to give the position the 24 hours, 7 days a week attention it demanded.

Values - Faith

Margaret:

I am a “cradle” Anglican.

Christianity teaches us that all of us are equal. To me that has always meant equality in every sphere. The step into social justice issues was absolutely logical, and necessary, to me. It brought my faith into the world – gave it life, and meaningful expression.

The desire to be an agent of change began for me when I went to England in the 1960’s and worked in a London “crammers” school tutoring classics. Inequalities were rife; supported and perpetuated by all pervasive class discrimination.

I remember reading William Temple’s book “Christianity and Social Order” around that time and being profoundly moved. What he said resonated and became a personal touchstone.

Archbishop of Canterbury from 1942-44, William Temple was a leader in the ecumenical movement and in educational, labour and social reform. His work provided the foundation of the 1942 Beveridge Report which led to the establishment of the UK Welfare State in 1945 – establishing the provision of universal access to healthcare, education, decent housing, proper working conditions, and democratic representation.

Archbishop of Canterbury from 1942-44, William Temple was a leader in the ecumenical movement and in educational, labour and social reform. His work provided the foundation of the 1942 Beveridge Report which led to the establishment of the UK Welfare State in 1945 – establishing the provision of universal access to healthcare, education, decent housing, proper working conditions, and democratic representation.

Much later I joined what’s known as The Third Order - a group of Anglicans who have dedicated themselves to live their lives in accordance with Franciscan principles. I find it a liberating God-centred structure. There’s strength in working together; alongside others who share similar beliefs and goals. I guess you could say my values are a fusion of socialism and Christianity.

- On the role of the law

Margaret:

... what does having a death penalty say about a society?

The structure of law itself can actively support people or hinder them because it echoes, or mirrors, as well as forming, the values of the society it springs from.

For instance what does having a death penalty say about a society?

Or, our need for FoodBanks? Helping feed those who are hungry is good, but asking and then practically answering the question; why do we need foodbanks in the first place?, solves the problem. I wanted to use my knowledge of the law to do that – to facilitate positive change.

- What personality or character attributes are needed to become a good lawyer?

Margaret:

It depends. There are different roles for lawyers requiring different attributes.

However the uniting characteristic I believe is “integrity”, being faithful to the higher purpose of the profession as well as having the perseverance and commitment required to put one foot after another to see whatever job is in hand through.

- What propelled you into the law?

Margaret:

Pure practicality! I was a classicist with a 1st class MA Hons in Latin and Greek, and small children. I wanted to work but I needed to change direction. I enjoyed the work I'd been doing with Amnesty International.

I am a long-time member and was part of an early group of Amnesty International in NZ in 1968. I was elected to Amnesty’s nine-member International Executive in 1999, a position I held until 2005.

I am a long-time member and was part of an early group of Amnesty International in NZ in 1968. I was elected to Amnesty’s nine-member International Executive in 1999, a position I held until 2005.

So when I was looking for something new I realized that qualifying in law would allow me to achieve much more and I’d become really useful. So I went back to university at Otago, fitting part-time study in around children. I was 32 years old and although I found it difficult to return to the discipline required, I loved it. It was exciting, invigorating and I’ve felt that way about law ever since.

- What roles have you had within law?

Because my career path was a road less travelled, it’s not a particularly useful model for anyone else to base their career plan on! Over the years I’ve had roles in three main areas:

- Academic law

- Semi- governmental – my years at the Commission

- NGOs, especially Amnesty International and the Human Rights Foundation

My thorough training in black letter law gave me a solid foundation. That also gave me a mutual meeting point, a common vocabulary, with other lawyers regardless of their fields.

Teaching law when I started at Otago in 1979 was very “newish” as a profession. The typical route for a lawyer had been through a type of apprenticeship – whereby you were employed as a law-clerk and studied part time. Gradually that changed and the whole of one’s training and study was completed at a law school. I came along on the cusp of that switch. I did spend some time as a law clerk prior to beginning as a lecturer.

Memories

- When you look back what memories come to the fore?

Margaret:

The first that springs to mind is working alongside Peter Hosking who was Proceedings Commissioner at the New Zealand Human Rights Commission from1988 until 1996. (He is currently Chairperson of the Human Rights Foundation.)

The first that springs to mind is working alongside Peter Hosking who was Proceedings Commissioner at the New Zealand Human Rights Commission from1988 until 1996. (He is currently Chairperson of the Human Rights Foundation.)

We attended the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna. I found it very exciting to be part of such a global human rights meeting. Women’s rights were a focus of that meeting and it was great to watch how the women from all levels, states, National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs), and Non- Governmental Organisations (NGOs), worked together there.

Peter and I were also both at the Paris meeting of NHRIs in 1991 which produced the Paris Principles.

Another is assisting to change the mandate of Amnesty International to include economic, social and cultural rights as part of the International Executive Committee from 1999 to 2005.

- What are you most proud of?

Margaret:

- The work at the Commission. The thrill of being part of a collaborative problem solving group from all sorts of areas where people brought all of their abilities to the table stays with me.

- Amnesty International’s mandate expansion. Amnesty International (AI) was coming under a lot of criticism for its sole focus on civil and political rights. I had seen that for myself when travelling around to various AI sections.

The Human Rights Foundations’s co-ordinating role in the case of Ahmed Zaoui. The Human Rights Foundation (HRF) had always done work on asylum seekers and refugees, but with the case of Ahmed Zaoui we learned so much more about the value of working in partnership with many other groups – and the part which lawyers can play.

The Human Rights Foundations’s co-ordinating role in the case of Ahmed Zaoui. The Human Rights Foundation (HRF) had always done work on asylum seekers and refugees, but with the case of Ahmed Zaoui we learned so much more about the value of working in partnership with many other groups – and the part which lawyers can play.

(The HRF was also involved in another collaboration: the book Law into Action, which was edited by Kris Gledhill and me, was the work of 26 authors from a variety of backgrounds and was intended as a guide for all manner of actors working in the field of human rights.)

Legacy advice

- What are your top tips for young lawyers?

Margaret:

- Establish a strong and broad foundation. I was always very grateful for my grounding in black letter law which is helpful if you move into newer areas of law, like human rights was when I started there in 1989.

- Recognize and take your chances when they come. Think them through, understand as far as you can, what you do, and do not, know, and then take them.

- What are your survival strategies for dealing effectively with stress?

Margaret:

Don’t take yourself too seriously.

- Make a space for yourself that is NOT law. It could be sport, or some other hobby. For me it was swimming – and reading novels. You need it for regeneration; for “breathing space”.

- Get yourself a supervisor; someone whose judgment and ethics you trust and set up regular meetings where you literally tell it all. It’s a safety valve.

- Establish “cut-off points”. These can be time-bound or physical. I found putting time limits on how long I would spend thinking about a particular situation useful. Similarly, when I was at the Commission I drove from my home into central Auckland. On the way back crossing the harbour bridge was my signal to get some distance.

- Don’t take yourself too seriously. It’s very tempting to begin thinking of oneself as extremely important with an equally extremely important and terribly serious job. You begin to think you’re indispensible! To maintain balance we need to keep a healthy distance from over identifying in the roles/titles we carry. We are always a part of something larger, a bit player, a person with a role. That’s all.

Legal issues

- What do you think are our top current legal issues, and why?

Margaret:

- The need for reform

We live in an increasingly divided society. I think it’s very distressing and of course damaging.

We know the structures of the law and of society are self-made; shaped, created and accepted by the society they support. We can change them, and thus change how people live. We’ve got examples of people who have used their positions to make a difference, for instance Peter Williams and his work for penal reform. There is similar work to be done in the disability and employment areas.

- The need for "decent" social policy

We must not lose the concept of a “decent” social policy. It must be inclusive of everybody, so that they can achieve to the best of their ability. We need structures to achieve that.

That includes our immigration policies with respect to refugees and asylum seekers.

- Our role on global issues

We may be an island nation but we live in a rapidly diminishing world. Hiding down in the bottom of the Pacific is no longer an option. Neither is tethering ourselves to a Big Brother. I believe we need to think through and act on issues, for instance climate change, development, peace-building and international citizenship, for ourselves.

Lawyers have a role to play in all these areas.

- Legal aid

I am concerned about the reduction of it, and the increase in difficulties of obtaining it. Those concerns have also been noted by others. They are spelled out in this recent Issue of Law Talk. It should be available for everybody who needs it.

- How law is made

We are seeing more legislation being rushed through under parliamentary urgency or through the diversionary tactic of using referenda. (A similar observation is made in this Chen Palmer column in 2011 )

Law should be made properly which means observing the democratic process, including using Select Committees, and allowing people time to exercise their democratic rights.

- Bypassing the law

Similarly concerning is the sacking of the democratically elected regional environmental council in Canterbury and appointment of Commissioners in 2010. Five years later democracy is still not restored.

- The need for transparency

- Trans Tasman Partnership. The secrecy surrounding it is another concern. Keeping debate away from Parliament and the people it serves is particularly worrying, as is the international arbitration system.

- Human Rights. Another example is NZ’s observance of the various International Human Rights Treaties we have ratified. We have an obligation to uphold them and yet there is a major gap between what we purport to support on an international level and what happens at home. As a recent study by Wilson, McGregor and Bell found, (reported on here by the NZ Law Society), we are not “walking the talk”. The areas pinpointed include health and disability law, the age of criminal responsibility, equal pay, Māori inequalities and prisoner voting rights. One could add others such as the lack of protection for economic, social and cultural rights in our constitution and our neglect of our overseas commitments on development.

Concluding thoughts

... we have forgotten about the “common good”

It concerns me that increasingly we as a country have taken onboard a debased and diminished interpretation of Adam Smith’s (The Wealth of Nations) doctrine. We accept and endorse his free market principles, refocused through self-interested neo-liberal lenses – stripped of the moral foundation Smith intended to support them. In doing so we have forgotten about the “common good”.

It concerns me that increasingly we as a country have taken onboard a debased and diminished interpretation of Adam Smith’s (The Wealth of Nations) doctrine. We accept and endorse his free market principles, refocused through self-interested neo-liberal lenses – stripped of the moral foundation Smith intended to support them. In doing so we have forgotten about the “common good”.

The concept of “free trade” has become a means to a very selfish and exclusive end, rather than an ideal, instrumental in uplifting society as a whole. It was never intended to be used against people. It was to be a way of gauging the effectiveness of an economy, broadly defined, and revising it if necessary to better serve its people.

Law is intimately involved in creating, supporting and advancing the society we live in. So we must use it to advance the common good. That is after all what human rights is all about.

Who would you like to see interviewed?

You are welcome to forward the names of people whom you think fit the title legal luminary. Please send your suggestions through the response form below. We look forward to hearing from you.