An interview with Professor Richard Boast, author of The Native Land Court 1862-1887

The Native Land Court 1862-1887: A Historical Study, Cases and Commentary, the first ever authoritative published selection of the Native Land Court's principal decisions will be available in November 2013. This landmark text explains the history of the Court and contains over 100 principal cases. The full text of each case is included alongside explanatory commentary covering the case itself and its historical significance.

The Native Land Court 1862-1887: A Historical Study, Cases and Commentary, the first ever authoritative published selection of the Native Land Court's principal decisions will be available in November 2013. This landmark text explains the history of the Court and contains over 100 principal cases. The full text of each case is included alongside explanatory commentary covering the case itself and its historical significance.

[caption id="attachment_5954" align="alignright" width="250"] Professor Richard Boast[/caption]

Professor Richard Boast[/caption]

Renay Taylor, Thomson Reuters Product Developer, who has been closely involved in the project, interviewed its author Professor Richard Boast (Victoria University Law School) for Online Insider.

(Renay's questions are in bold. Professor Boast's responses are below each one.)

Could you tell us a little about yourself?

We'd like to know where you were born, grew up, went to school, university, and what was your first job.

I was born and raised in Tokoroa, a country town not far from Rotorua – a place based on forestry and farming. Like a lot of people in Tokoroa my parents were migrants from the UK. I went to primary and high school there, then headed up to Victoria University in Wellington in 1973 to do a BA and my LLB, I finished my BA in history in 1975 and my LLB in 1977. My first job after I graduated was as an assistant lecturer at Vic, where I stayed for three years tutoring in introductory law subjects and working on my LLM thesis. My wife Deborah and I moved to Hamilton in 1981 where I worked as a solicitor in a Hamilton law firm and then practised there on my own account as a barrister, concentrating on criminal law and environmental law. Our first child, Hannah, was born in Hamilton. While in Hamilton I completed my LLM and did an MA in history from Waikato University. We returned to Wellington in 1986 and I have been at VUW Law School since then. Our son Alex was born in Wellington at the end of 1986.

What do you do now?

Now I divide my professional time between teaching, barristerial work and giving expert historical evidence, which I’ve done in the Maori Land Court and Waitangi Tribunal. As for my personal time I enjoy travel, especially to Latin America, and spending time with my granddaughter and our two border collies. Two of my areas of special research interest are legal history and Maori legal issues – I’m enjoying being able to work on a project that brings the two together.

One of your areas of special interest is Maori Land Law.

How did you first get involved in what must have been a very niche area at the time?

It was a very niche area back in 1980s! I did some work with Maori clients on land issues when I was in legal practice in Hamilton, but it wasn’t until I started as a full time lecturer at Victoria University that I really started to get involved. My first big case in the Waitangi Tribunal was in the Pouakani case around 1989, I was co-counsel in that case along with Paul Heath, who is now a judge of the High Court.

When did you realise that you were going to build your career around Maori Land law and its history?

[caption id="attachment_5957" align="alignright" width="200"] Francis Dart Fenton, first Chief Judge of the Native Land Court. Photographer unidentified. Reference: PAColl-7489-01, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ[/caption]

Francis Dart Fenton, first Chief Judge of the Native Land Court. Photographer unidentified. Reference: PAColl-7489-01, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ[/caption]

The point that stands out is when I came back to Vic and was teaching Public Law in ’87 or ’88. I was going through some of the Waitangi Tribunal decisions (there were not many in those days: it was all very new) and read the Manukau Report – what struck me was the New Zealand specificity of the law, that it’s ours and not replicated anywhere in the world. That was what I most liked about it. Since then it’s been one of my dominant areas of interest and research.

What inspires you to work in this area?

I’ve always found it scandalous that early judgments of the Native Land Courts can’t be accessed unless you physically travel to their location (with the exception of Chief Judge Fenton’s publication in 1879) or you obtain them from a research library such as National Archives. So part of what inspires me is the access to this history and the need to understand – how can we understand the processes if we can’t find the judgments? How can we understand what happened historically between Maori owning their land and then not? How can we understand how it works today without access to the past?

Can you choose a moment from your career so far that has been a highlight?

I can choose two. The first is when I gave evidence about the 90 Mile Beach decision at the Waitangi Tribunal. I had to go back and look at the early land records – from them came the conclusion that the law about the New Zealand foreshore and seabed was based on completely wrong foundations. I can remember very vividly giving evidence on this to the Waitangi Tribunal, this would have been around 1991. I think that the Tribunal was as surprised as I was. In the end the Tribunal didn’t have to decide on this, but of course the foreshore and seabed issue has never gone away.

And winning the Montana Book Award for History for my book Buying the Land, Selling the Land in 2009 was a very proud moment. I thought it was a recognition of the work that has been done in this area in recent years by many historians, not just myself – I could never have written that book without all the new research being done by historians who have been doing work for the Waitangi Tribunal inquiries (that is why I dedicated my book to them). And the same goes for my new book on the Native Land Court. Without all the new work done by many researchers it couldn’t have been done at all.

Of the many marae you have visited, is there one that stands out in your memory? Why?

The most memorable is Waiohau, between Whakatane and Murupara. The dignity and tragedy of the story told at the marae, of how Ngati Haka Patuheuheu were evicted from their ancestral home of Waiohau Block and moved to the present site all because of a Native Land Court jurisdictional mistake is a vivid memory. There was legal decision about it called Beale v Tihema Te Hau which I include in the course materials for my part of the Property course at Victoria University. It’s a story which needs to be better known.

What are the challenges of researching and writing on Maori land and legal issues?

The complexity of the law is a major challenge – Sir Robert Stout once commented that he couldn’t understand the Native Land Court legislation, which didn’t bode well for the rest of us! Finding the content is also a challenge, there are literally thousands of pages of handwritten manuscript that make up the NLC minutes.

[caption id="attachment_5961" align="aligncenter" width="500"] Sitting of the Native Land Court at Ahipara, Northland, 1904. Reference: AWNS-19051027-11-1,

Sitting of the Native Land Court at Ahipara, Northland, 1904. Reference: AWNS-19051027-11-1,

Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Public Libraries.[/caption]

In a modern context, the contentiousness of Maori politics, especially over interests in land, is always in my mind: these battles are still being fought in court, they are still the cause of much debate. The struggle is to keep entirely neutral and to appreciate that there are two sides (or sometimes more than two sides) to be told about all of these land blocks. I believe that non-Maori scholars should try hard not to take sides over complex matters of traditional history. I see my new book as a book about the Native Land Court as an institution, not a book about Maori traditional history or custom – these are fields I leave to others. I do include material from the evidence in Court in my essays on the cases, but only in order for it to be seen what the case was about. The Native Land Court had some ideas about Maori custom, but in my view the Court never really developed a sophisticated body of law about this, it was all surprisingly ramshackle.

There have been major legislative and case law developments in Maori land and legal issues over the last decade.

Have you noticed a change in legal and academic attitudes towards Maori legal issues? In what way?

Definitely. For one, I can remember in my own law degree that Maori Land and legal issues just weren’t there; they weren’t even on the radar. I don’t think the Treaty was even mentioned.

Now it’s become more mainstream in the sense that there are several specialised papers offered at each law school as well as being factored into the compulsory courses. There are many more Maori judges, lawyers, and legal academics these days. At my own school there is a lot of really interesting and innovative new research going on, including a new Maori legal dictionary.

In your opinion, how do you see Maori land law developing over the next decade?

I expect that there will continue to be major changes over the next decade, for example the review of the Te Ture Whenua Maori Act. There’s a perception in government that it’s too restrictive, and in some respects I agree with that, but in my opinion any reform needs to be handled with caution or it won’t last. The Maori land system has been around a long time. Any major changes made to it now require a great deal of careful thought and consultation with everyone affected. The history shows us that there have been many bungled “reforms” in the past, we don’t want to make those sorts of mistakes again.

Another major change may come about once all the regional enquiries by the Waitangi Tribunal are complete and a decision is made about the future role of the Tribunal. Also there have been many negotiated settlements of historic grievances by now, it will be interesting to see what these will lead to.

Your current work on the Native Land Court combines Maori Land Law and Legal History.

Who do you consider to be the greatest character (or leader) of the Native Land Court and why?

The Native Land Court was full of interesting characters. The Judges were a diverse bunch – there was no need to be a lawyer – they were from all walks of life. Chief Judge Fenton has to be one of the greatest characters though. The history books are often hard on him as being anti-Maori, but he was a complex man and some considered him too “indulgent” (i.e. towards Maori) at the time. He was a classic Victorian achiever – a solicitor from England who ended up as Chief Judge of the Native Land Court in New Zealand. One thing about him is that was a very good lawyer, in the technical sense.

It strikes me that there was more to the man than Fenton the Judge. In the 1880s he was part of a project to have Maori Land leased. At a meeting to celebrate (prematurely, unfortunately – the project ended in disaster) Fenton did a haka with the local Chiefs which makes me think they must have had a mutual respect for each other.

Do you have a favourite historic case? Which one and why?

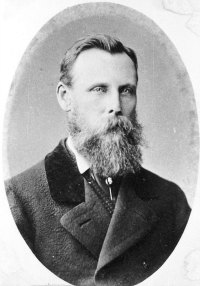

[caption id="attachment_5959" align="alignright" width="200"] William Lee Rees, lawyer and Liberal politician. Photographer William Henshaw Clarke. Reference: F-147-35mm-B, General Assembly Library Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.[/caption]

William Lee Rees, lawyer and Liberal politician. Photographer William Henshaw Clarke. Reference: F-147-35mm-B, General Assembly Library Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.[/caption]

The Chathams case – it’s the most dramatic because the issue was the conquest of the Moriori by Maori from Wellington. There’s a dramatic account of the conquest from Ngati Mutunga, and tragic evidence on behalf of the Moriori. It’s interesting, too, because it involves an indigenous group that aren’t Maori.

If you could go back in time and meet any party from any case, who would you choose and why?

I would very much like to meet William Rees, a lawyer who seemed to be involved in everything up and down the East Coast in the 1880s and 1890s. He was a bit of a radical for the time, appearing in commissions, enquiries, trusts, politics and a number of recorded cases. A one man hurricane! He worked with Wi Pere setting up the East Coast trusts, which became a gigantic fiasco.

What I like about him is that he gives us a snapshot of Pakeha and Maori working together. I think that if we could find out what he was up to we would have a good idea of what made 19th Century New Zealand tick.

What is the significance of the Native Land Court to contemporary Maori Land Law?

It’s pivotal. While the Waitangi Tribunal consider key cases (as in the Chatham Islands Report) the Maori Land Court itself does not cite relevant decisions from the early days of the Court – the minutes are too hard to find. But the basic ideas, the framework, laid down in the early Native Land Court days are still the framework for today – like the “1840 Rule” which can be traced directly back to the first years of the Native Land Court, the various kinds of cases that the Court hears, and even its style of record-keeping. Of course there have been many changes as well.

And finally, where will your research be taking you next?

Well I’m already working on a second volume of The Native Land Courts, which will take us up to 1910.

And I was very fortunate to receive a grant from the Marsden Fund last year to research changes in land tenure around the Pacific, including Mexico, Hawaii and Tahiti, to compare with New Zealand. That’s going to keep me busy for the next three years!

For more information about the book or to pre-order ...

The Native Land Court 1862-1887: A Historical Study, Cases and Commentary