The price of milk - Penny Mudford

The spectacular rise, followed by the equally spectacular fall, of the dairy industry means arbitrator and mediator Penny Mudford is contacted more frequently to help negotiate and settle disputes.

Despite what many people outside of the industry say, there is no one particular cause to blame, says Penny, for dairy farmers getting into difficulties. Certainly, the current farmgate milk price is a significant factor but farming businesses are complex and no two farms are the same. In her opinion the severity of the current financial situation on farm was unforeseeable.

Despite what many people outside of the industry say, there is no one particular cause to blame, says Penny, for dairy farmers getting into difficulties. Certainly, the current farmgate milk price is a significant factor but farming businesses are complex and no two farms are the same. In her opinion the severity of the current financial situation on farm was unforeseeable.

Quick facts

• Farmgate price = $ per kg of milk solids

• Fonterra collects 87% of all milk produced

• 95% of all milk is exported

Reasons for downturn

• Global volatility - reduced demand from China, Russia & Europe

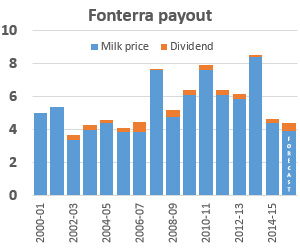

Ups and downs - Fonterra payouts

If we look at Fonterra payouts (milk + dividend) from 2002 to the present we can see that the current payout is less than half the peak of $8.65 in February 2014, and 20% less than the $5.35 paid back in 2002. She says that the payout farmers receive has always moved up and down but a fall from $8 – $9 to around $4 over two seasons is difficult for any business to manage.

If we look at Fonterra payouts (milk + dividend) from 2002 to the present we can see that the current payout is less than half the peak of $8.65 in February 2014, and 20% less than the $5.35 paid back in 2002. She says that the payout farmers receive has always moved up and down but a fall from $8 – $9 to around $4 over two seasons is difficult for any business to manage.

Dairy farmers are used to dealing with ups and downs, with shifting volatility in the global marketplace, she says, but the depth and persistence of the current downswing has taken many by complete surprise.

On farm costs, says Penny, have not conveniently shrunk alongside income. The result for many in the dairy sector is that their previously viable farming business is now not so viable and, in some cases, insolvent. It is unfortunate, yet inevitable, that there will be difficulties and casualties. And, along with this financial stress comes considerable emotional and psychological stress on farmers and their families.

Gaining control

One of the hardest steps to take is often the first one.

One area that is particularly difficult, says Penny, is on farms where sharemilking agreements are in place. These are used when a farm owner and a sharemilker ‘share’ the roles and responsibilities of the business and its operation.

The farm owner is the person (or business) who owns or leases the land that the dairy farm business uses as a base for its operation. The sharemilker is the person (or business) who runs the farm operations. The dairy cows are either provided by the farm owner, the sharemilker, or by both and sometimes they are leased rather than purchased. Other factors critical to the dairy operation (for example, responsibility for the purchase of fertiliser, ongoing maintenance, and crops) are allocated to either the farm owner or sharemilker and sometimes shared.

When farm businesses contain these layers of complexity there is plenty of opportunity for dispute if one party is unable to afford to fulfill their obligations under their sharemilking agreement.

One of the hardest steps to take, says Penny, is often the first one. That is, she says, to recognise and acknowledge that the gulf between operating costs, debt servicing and income has become too big to bridge.

People under stress tend to hope against hope that the situation will change – that they will be able to weather and endure the situation without having to make significant changes.

Once that is no longer possible then they stop spending money on operating costs. This, says Penny, can often results in counter-productive decision making, for example, not applying fertiliser or laying off staff. Regardless of farmgate price, stock needs feeding properly and machinery must be maintained. Cutting back on veterinary care, reducing supplementary feed, or foregoing routine maintenance is not a viable answer.

Understanding the contract

...the devil is in the detail

One of the first places to begin, says Penny, is to fully understand the legal position –the sharemilking agreement and financial arrangements with the bank. When things are going well there is a tendency for people to coast along unaware of the full legal implications of the documents they’ve signed. However, she warns, when times are tough and when it becomes much more difficult to deliver on legal obligations, the devil is in the detail.

The role of warranties

Sharemilking agreements tend to be based on a farm’s historical performance and use warranties guaranteeing its ongoing performance. These specify, for example, the number of animals the farm can hold and the level of milk production likely to be achieved. Because warranties are fixed in the past, rather than what is happening now, they can sometimes be unrealistic.

For example, a farm may have previously produced high volumes of milk with the help of supplementary feed which is no longer affordable on the current payout price. The consequence may be that without the additional feed the farm is not able to produce as much milk thus affecting the businesses of the farm owner, and the sharemilker. Who is liable for the loss of milk production in a situation that is certainly going to have cashflow consequences for both parties?

Recording variations to the written agreement

...easy going arrangements and mutual trust can be the first causalities when the going gets tough.

Sharemilking agreements are commercial contracts containing comprehensive terms intended to provide clarity on every aspect of the dairy farm operation. A further complication that arises, says Penny, is when variations to the agreement are made but are not recorded in writing. Instead there are a series of unverifiable “he said, she said” assumptions. Penny says easy going arrangements and mutual trust can be the first causalities when the going gets tough. When livelihoods are threatened people quite naturally look to protect their interests and preserve their incomes. Establishing what was agreed becomes vitally important when disputes arise, she says. In these cases, says Penny, everything revolves around the contract – what is in it, and what is not. If a dispute ends up at arbitration, the fact the milk payout has fallen significantly with implications on the farming operations has no relevance to the signed sharemilking agreement. Generally if any alterations are going to be judged valid they need to be in writing.

Seeking advice

... a practical plan and support from others that is going to get people through

Industry leaders are increasingly aware of farmers in difficulty.

A Federated Farmers poll in February revealed one in ten dairy farmers are under pressure from banks over their mortgage and those who already have special arrangements in place to carry them through 2015 may be unlikely to have them extended.

Rather than waiting for the axe to fall, Penny says it is much better for people to initiate taking action themselves. If they do nothing, she says, others are likely to make their decisions for them.

Seeking advice and practical help will not remove or solve all the problems but it will at least provide a managed way forward. Farmers, she says, have the best chance of surviving the down swing if they actively work with their farming partners, farm advisors, and banks to formulate a plan for getting through the season. What’s needed she says, is a level headed pragmatic approach. Even though the situation triggers an enormous range of understandable emotional responses – fear, anger, distrust, despair – it is a practical plan and support from others that is going to get people through.

Do not wait

Waiting for the season to end before attempting to sort something out will not work. And, as sharemilking agreements generally have clear time limits set down for making claims it is important to ensure that any claims that either a farm owner or sharemilker has against the other are made within the time limit set out in the contract. Failure to do so may result in claims being rejected.

Contracts can be renegotiated, says Penny, and if changes are made then the new agreements need to be recorded in writing.

Where parties cannot agree to modify existing contracts there are options, says Penny. Seek experienced and skilled people to help with discussions and negotiations between farmer and farmer, or farmer and bank. For example, presenting a survival strategy may stave off the inevitable consequences of waiting until it is too late.

The links below are all good starting points.

- Rural Support Trust offers understanding and practical support at a regional level. Their coordinators are experienced in helping people facing challenges in farm management and finance. They can refer people on if necessary.

- Federated Farmers offers free advice to all its members across a broad range of areas including legal issues.

- LIC offers advice for “tough times”.

- DairyNZ offers support for sharemilkers.

- National Panel of Conciliators has skilled people to help with disputes.

New agreements

If entering into a new agreement, Penny says it is imperative to consider the total costs involved. These include looking longer term at the potential downstream consequences of low payout seasons. There are questions to ask, she says, around sustainability. Are the targets in the agreement realistic? Do we have a sound financial management plan in place to meet that? Can we sustain a reasonable lifestyle for ourselves, our families, and our employees?

Downstream consequences of the downturn

No one is immune

The industry is experiencing falling land prices and an increasing number of receiverships. Many people are leaving, some voluntarily, while others are being forced out due to their circumstances. Inevitably the squeeze extends to all the businesses and services associated with dairying communities. No one is immune, says Penny.

About Penny Mudford

Penny has extensive experience in the dairy industry; both as a farmer and in dispute resolution as an arbitrator, conciliator, and mediator. She is a Fellow of the Arbitrators’ and Mediators’ Institute of NZ and is a member of the National Panel of Conciliators. Her most recent work in the field is to update her chapter on “Rural Arbitrations” in the Green and Hunt on Arbitration Law and Practice.

Penny has extensive experience in the dairy industry; both as a farmer and in dispute resolution as an arbitrator, conciliator, and mediator. She is a Fellow of the Arbitrators’ and Mediators’ Institute of NZ and is a member of the National Panel of Conciliators. Her most recent work in the field is to update her chapter on “Rural Arbitrations” in the Green and Hunt on Arbitration Law and Practice.

She can be contacted via her website Resolution World.

References and Resources

- Dairy pay out history – interest.co.nz

- Dairy downturn knocks farmer’s confidence – Rural Business – NZ Herald

- Analysts predict dairy disaster ahead – Stuff

- Dairy leaders urge farmers to help sharemilkers – Stuff

- Managing the dairy downturn - Keith Woodward -Honorary Professor of Agri-Food Systems at Lincoln University

- Businesses feel effects of dairy drop – Survey - Radio NZ News

- Gone Broke 0800cowcocky – interview – Country Life – Radio NZ