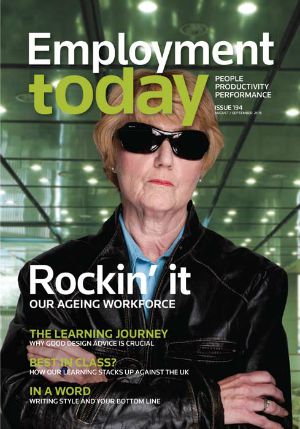

Surfing the ageing wave

There’s no getting around the fact the New Zealand workforce is ageing, but are our organisations prepared for what’s ahead? Yvonne van Dongen looks for answers.

At 65, early childcare worker Hetty Ellis continues to work at the Auckland Girls’ Grammar Childcare Centre where she’s worked for the last 20 years. “I love the contact with colleagues. I love the kids to bits and it’s nice to get a bit of pocket money, but that’s not the main reason, since you don’t get paid a lot in daycare.”

But Hetty works on her terms. She works two days a week and is on call the rest of the time. “The best thing is I can always say no.” She can also take extended time off to visit family in Holland. It’s an arrangement she’s had for 10 years now and she says it’s probably one reason why she’s clocked up two decades at the same centre. Hetty is not sure how long she’ll continue to work, but she’s grateful there’s no pressure from her boss to retire.

“When new parents come in, my boss always introduces me as ‘Hetty who’s been here a long time’. I think she sees the benefit of continuation.”

However, Hetty acknowledges there are things she struggles with as an older worker. “The noise, the giving, giving, giving. I couldn’t work full-time. I get too knackered. It’s tiring working with children.”

But for an older person in the workforce, Hetty has struck gold. She has achieved what most of this demographic regard as the most critical requirements when it comes to remaining in the work-force—respect and flexibility.

AUT Business School’s Professor Tim Bentley has just completed a study of 1200 mature-aged workers, that is those over 55, in different organisations throughout New Zealand. “We asked what they wanted most to stay in the workforce. Sixty percent said respect and recognition was number one. Second was flexibility—that is, the ability to go part-time, work from home or adjust their working hours to meet their lifestyle.”

As a low-waged childcare worker, Hetty can’t cite money as being a prime driver for her continued employment, but Bentley says for many older workers, some hit by the GFC, extra income is definitely a factor in their decision to continue working.

Bentley’s study showed that although almost 60 percent of workers said they’d like to retire by 65, only 45 percent thought they would be able to. That means we can expect more workers aged 65 and over still in the workforce in the coming years.

Already New Zealand has the second highest employment rate of people between 55 and 62 years of age, and the third highest among those aged 65 to 69 among OECD countries.

That the New Zealand workforce is ageing is inarguable. In 2012, 50 percent of the labour force was older than 42 years of age, compared with 36 years in 1991 and 39 years in 2001. As at June 2014, 22 percent of workers were aged 55 years or over. Research indicates that by 2031, New Zealand will be home to more than a million people aged 65 and over—that’s one in every five people. By 2051 that will be one in four people.

A recent Chandler MacLeod Group company report on the impact of the ageing workforce on New Zealand business revealed that although almost 60 percent of employers believe an ageing workforce will have a large or very large impact on their own organisation, in practice they’ve done little about it.

Bentley warns most organisations won’t be able to dodge the inevitable decline of the baby boomer bulge, but that this ageing workforce presents both opportunities and problems.

Precious knowledge and experience

The most pressing problem is, obviously, a growing skills and labour shortage. Departing workers will take precious knowledge and experience with them and won’t be replaced by the upcoming and smaller workforce. This will hit some sectors more than others. Those most at risk were identified in a report by Dr Judith Davey, now at Victoria University but formerly a director of the New Zealand Institute for Research on Ageing.

Many were in the health sector (nurses, midwives, GPs, dentists), the academic world (teachers, lecturers), the public service sector, architects, some engineers, social workers, bus drivers, religious professionals and crop, livestock and mixed livestock producers.

Bentley says there are three key ways to deal with this shortage—immigration, encouraging women to return to the workforce and retaining older workers longer.

But age discrimination, based on myths and stereotypes, may be a barrier to achieving the last two goals. Older workers are regularly viewed as less adaptable, less technology savvy and difficult to train. They’re also perceived to have declining physical health and cognitive functioning and be more susceptible to work-related stress. Both employers and workers can fall victim to these prejudices.

Barry, a buyer for a food company, says his employers tried to push him out in favour of a younger friend of the boss. He dug his toes in and stayed for another five years because he loved the work and, at 70, he reckons he’d still be there if it wasn’t for his wife urging him to stop.

But as Nicola (not her real name), a former senior journalist, reports, it’s hard to pinpoint whether your failure to progress in a workplace can be attributed to an age prejudice, general sexism or possibly being outgunned by other workers. Nevertheless, she believes she was overlooked for promotion in favour of younger employees. After years of frustration she left her workplace, but found it hard to even get an interview for positions she felt well qualified to handle.

“I’m 58 now and I’m pretty sure my age is against me, but it’s impossible to be sure of course since discrimination on the basis of age is illegal, so no one’s going to come out and say ‘You’re too old’.”

Others in the media report that employers get around that by advertising for “digital natives” or “people with three year’s experience”, thereby effectively elbowing older workers out of contention.

But like all stereotypes, HR managers, employers and employees report there may be some truth to some of the negative perceptions about older workers. Although it’s widely agreed older workers can contribute much to the workforce, factors affecting their willingness and ability to work include poor health, financial circumstances and family responsibilities.

In Davey’s study, some cited feeling burnt out and fed up by the continual change in the work-place. They felt cynical and had lost interest in their job. For a few, work felt like a treadmill. She found some employers felt older men did not take well to having younger managers, and there may be problems fitting into “the culture of young bright people”.

Hetty remembers an older woman at the centre who couldn’t cope with the stress of working with small children. She eventually left of her own accord. Elsewhere, an HR manager at a major hospital reported that the average age of the nurses employed at her place of work was 54 and, while they were experienced, older nurses often struggled with the physical demands of the job. The hospital didn’t always have enough hoists to lift patients and some older nurses simply refused to do any lifting.

The HR manager was adamant she didn’t want to be identified. The issue was too sensitive and “nurses are very emotional people.” She acknowledged the impact of the looming skills shortage in the nursing profession, but says her employer has yet to address the issue.

The problem is tarring all older workers with the same brush. At NZ Post, where 1500 workers are 55 and over and 63 are 70-plus, age is not an issue. Says HR manager Sally Sexton “As long as the people are physically and cognitively able, NZ Post values their contribution. And that’s not just lip service. That’s true.”

Older NZ Post workers are employed in a variety of roles ranging from posties to mail office workers and administration staff. Some work full-time, some part-time. Where possible, NZ Post likes to accommodate their changing requirements.

And while the company is aware of talk of the looming skills shortage, “it’s not happened yet and it’s hard to know exactly what will happen in the future. We have been thinking about it though and we try to make sure we take on a range of people, that is, a range of ages and at different stages of their career. We’re lucky because we’re so large, we can be more flexible than smaller places.”

Taking steps

The Ministry of Health is also aware of the ageing workforce with 27 percent of its workers aged 55+. It is taking steps to retain health workers, to train enough new ones and lure others back from overseas. Adding to the inevitable decline of the baby boomers is a growing shortage in the Australian nursing work-force which is bound to put pressure on our health sector as some employees are lured across the Ditch, says Ruth Andersen, MoH Health Workforce NZ group manager. However, she is confident enough is being done to cope with the ageing workforce in New Zealand.

The practices of NZ Post, the Ministry of Health and Auckland Girls’ Grammar Childcare are in line with the findings of the latest Pricewaterhouse Coopers Golden Age Index. The report released in June this year revealed that New Zealand came second behind Iceland in the survey tracking employment of workers aged 55 across 34 OECD countries. Next were Sweden, Israel, Norway and Chile, with Australia at number 15.

But while this is encouraging, CEO of the Human Resources Institute of New Zealand Chris Till is concerned many companies may be practising “age wash”.

“I would suggest they are not prepared. The New Zealand Diversity Survey revealed that 68 percent of companies had no programmes or policies in place to deal with the ageing work-force. And while our ranking second on the Golden Age Index is good, we have to ask what kind of work are these people in? Is it well-paid? Regular? Secure? Unfortunately New Zealand does not have a culture or history of good leadership.”

He cites a 2015 Business of Ageing Update done by the Ministry of Social Development which reports that, by 2030, 30 percent of people aged 65 and over will still be working. But by 2050 that figure will rise to 65 percent of men and 55 percent of women aged 65-69. What’s more astonishing is that 12 percent of men and 10 percent of women over the age of 80 will also still be working.

This bodes well for the New Zealand economy. PWC chief economist and report co-author, John Hawksworth, says older workers are critical to boosting economic output. What’s more, New Zealand is now being regarded as a benchmark for Australia to follow. In fact PwC’s global people business leader Jon Williams estimates that if it could match New Zealand’s mature age employment rate, Australia could generate an annual average increase of NZ$26.9 billion in nominal GDP.

In addition, the report suggests there is a positive correlation between the Golden Age Index and life expectancy, implying that countries where people live longer also tend to have longer working lives.

The report also noted that the traditional view that older workers blocked younger employees from rising should not be the case. People working longer will have more income to spend. This extra spending will produce more demand for labour to produce more goods and services. The Business of Ageing report estimates that the mature consumer market will spend about $65 billion in 2051—a rise from about $16 billon per year currently. Thus the total number of jobs in the economy should rise to match the increase in labour demand.

This process will be aided if companies move away from linear seniority-based career paths to part-time or advisory roles for older workers. Here the report concludes New Zealand could do better. The country was 13th when it came to the incidence of part-time work for 55-64 year olds.

It’s clear from the PWC report that retirement is changing. Andrews says we may see the end of retirement as a one-time event and the beginning of the rise of the part-time pensioner.

The company identified seven steps to keeping older workers, starting with financial incentives, more training including digital skills, encouraging recruitment, boosting employment rate of older women, a tax rebate for companies taking on older workers, enforcing age discrimination laws and more flexibility.

Accommodating employment policies are working for Hetty Ellis who reckons she rates highly on the Golden Age Index. She says she’s not sure how long she’ll continue to work her part-time flexi hours at the daycare centre, but for now the combination is perfect. “I just love it.”

YVONNE VAN DONGEN is an Auckland-based freelance journalist.

YVONNE VAN DONGEN is an Auckland-based freelance journalist.

Read more Human Resource articles

This article, "Surfing the Ageing Wave", is one of three free-to-browse from the current issue of our HR magazine: Employment Today.

Check out

- The learning journey - A training course or an e-learning module only goes part of the way to transferring learning to the workplace, says Anna Kingston. To deliver sustainable results, we need to follow good design advice and create a learning journey. Read more.

- Talent strategy—Improving the candidate experience - The candidate experience is more important than ever in 2015, says Jason Marra. A positive one can win you the best talent, but a poor experience can damage your brand. Read more.

Thomson Reuters offers a full range of solutions for HR professionals - Find out more